|

Mongolia was the first asian

and buddhist land I visited. It was the first very different country,

and at the end of this trip, it remains unlike any other thanks its

unique way of life and traditions, and its history. I met 4 other travellers

in Ulan-Bator, and we arranged our trip via our guesthouse. Peg, from

the U.S. was teaching english in Mongolia and had learn some mongolian,

Tim from England, Roger and Fatima from Sweden were travelling just

like me. For a week, we bounced around in a 4x4 van across the steppe

and the desert, led by our funny mongolian driver. Every evening, he

would found in the middle of nowhere a "ger" (see note 1), the round tents you can see

everywhere in Mongolia, where there are people that is. For a week,

the nomads offered us their unforgetable hospitality and an unequalled

insight into their way of life and their traditions, so alive and so

fascinating. Mongolia remains one of the places I loved the most in

the whole trip. Here is why...

When we arrived at a ger at dusk, we offered a few

simple gifts. Like in many asian countries, offering and receiving something

with both hands is a sign of respect. The left hand, considered impure,

should never be used in such situations and especially not to eat. Thus,

our small gifts (a bottle of "arkhi", mongolian vodka, a bar

of soap, a lipstick, a pen and a notebook, and a postcard) were offered

to our host or to the eldest person. The gifts were redistributed to

the members of the family : the vodka (always shared with us later on)

was left within easy reach, the lady received the bar of soap and the

lipstick (which she would wear next morning when we took some photographs),

and the kids were happy to start scribbling with the pen on the notebook.

The postcard, a view typical from Mongolia, nothing unknown to them,

nevertheless captured the attention of the whole family. It was then

placed carefully on a frame, on the only one piece of furniture at the

back of the ger, along with photos and other postcards.We regretted

not having photographs or postcards from our respective countries to

show them.

While the tea was being prepared, we played dice or

card games with our host and the kids, who were quick to learn the rules

and eager to play. They also taught us a game with knuckle bones. Mongolian

tea is not your usual cuppa. A handful of small twigs (rather than leaves)

are boiled for a while in much water, then a laddle of milk (from cow,

camel or goat) is added along with a pinch of salt (it's not so bad).

The only one stove is dung fired (no wood around here) and cooking followed,

inevitably mutton and rice, mutton and noodle, sometimes potatoes with

mutton (fatty chunks rather than meat, as a sign of honour for us, boiled

and served as a soup). Toasting with vodka was soon a well practice

procedure. Bottles with capsules, once open, must be finished. Only

one glass passes around. First, the host or the eldest person dips the

right hand third finger in the glass, and throws a few drops in the

air, "to the sky", a few to the ground, "to the earth",

and a few towards the rest of us, "to the people". He or she

the downs the vodka. The host fills the glass again and then passes

it to each of us in turn, offering with the right hand, the left hand

under the right elbow, and we receive the same way. It is impolite to

refuse in Mongolia. When Roger proposed a cigarette to our host who

did not smoke, he took one out of the pack, and then with a smile and

a wave of the hand, put it back in. He did not refuse. We were offered

once a bowl of "airag" (fermented mare's milk, a slightly

alcoholic, slightly fizzy but very bitter product) from which each we

took just a sip, leaving the son of our host to down the rest.

I was in Mongolia at the

beginning of October. The Gobi (see note 2) was

still quite mild during the day but the steppe further north was already

getting seriously cold, covered by a layer of snow 5 - 10 cm thick in

some places. The ger, heated by the stove, was pleasant, but outside

it was probably down to -10 deg after dusk. This did not stop the wife

of our host to step outside in a T-shirt to pick up some dung for the

fire. The ger being round, with the stove in the middle and sometimes

two beds on either side near the wall, we had to work out which layout

was best to fit the 6 of us (including the driver).This space is normally

occupied by 4 or 5 members of the family. We lied down on the ground

on thick sheep skins, wrapped in our sleeping bags and covered with

more sheep skins by our considerate driver. Indeed, the fire was not

always kept going all night.

In the morning, breakfast (see dinner for the menu)

was prepared by the wife of our host, while our driver was busy heating

up the engine of the van with his scary kerosene blow-torch (also used

to cook lunch on the road). We washed our faces rapidly in the freezing

morning air with ice cold water.  Toilets were about 50 m away in any

direction, behind a few taller blades of grass (sometimes there was

a hole in the ground, surrounded by a few planks to hide it a little).

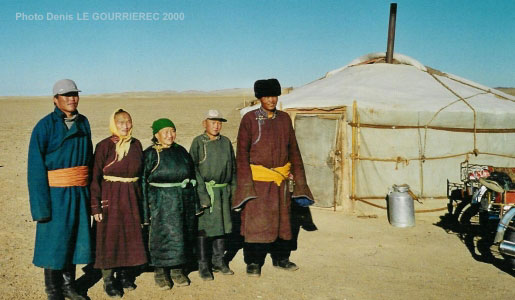

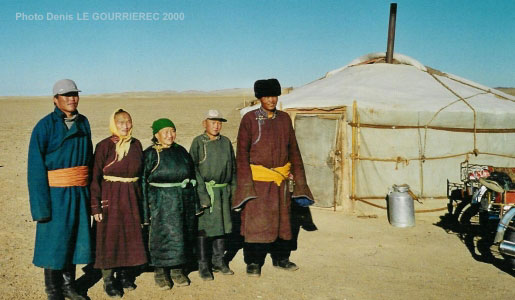

As

we started our breakfast, the van accepted to start and our driver joined

us with a triumphal smile on his face. We never left before taking some

pictures, our hosts always proud to pose for us and with us in front

of their ger, on their motorbike or on their horse. I have never seen

people so happy to have photos taken. It will be difficult for reprints

to reach them, but it is worth a try, since they will be so happy to

receive some pictures. Then we were ready to set off. Toilets were about 50 m away in any

direction, behind a few taller blades of grass (sometimes there was

a hole in the ground, surrounded by a few planks to hide it a little).

As

we started our breakfast, the van accepted to start and our driver joined

us with a triumphal smile on his face. We never left before taking some

pictures, our hosts always proud to pose for us and with us in front

of their ger, on their motorbike or on their horse. I have never seen

people so happy to have photos taken. It will be difficult for reprints

to reach them, but it is worth a try, since they will be so happy to

receive some pictures. Then we were ready to set off.

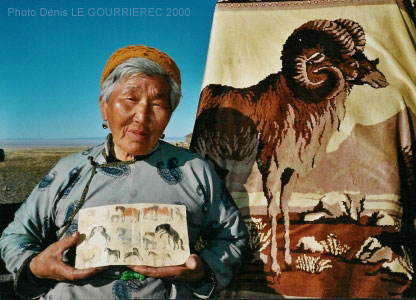

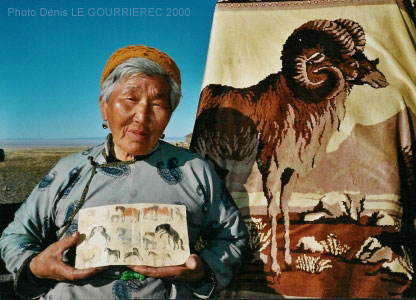

One of our stops was a little different. The lady

was living with her grand-son only, as the rest of the family was away

with the cattle (see note 3). Instead

of a ger, she was living in a small hut, with ... a solar panel on the

roof, a battery, therefore electricity and even a small TV set. In the

morning, she asked us to take some photos of a painting with horses

done by her late father. The colours were fading with time and she wanted

a copy. As we were leaving, we caught through the fogged up windows

of our van, a traditional and most beautiful gesture from her, as she

threw a laddle of milk in our direction, as a sign of blessing.

see more photos from Mongolia

__________________________________________________________

Note 1 : Pronounce "gair". The word "yurt" was

introduced by the russians and is not used by the Mongols, but by the

Kirghiz and the Kazakhs.

Note 2 : The Gobi is not a sand desert as often pictured,

but rather a vast and arid yet diverse expanse. The landscape sometimes

seems endlessly dead flat and the ground is covered in small dark pebbles

or dotted with with small dry shrubs, then a few hours further it becomes

more hilly or mountainous. In the south a huge sand dune (800 high,

100 km long, 20 km wide) stretches to the horizon. But I only saw a

fraction of this immensity...

Note 3 : The steppe can accomodate cows, horses, sheeps and

goats. The Gobi, being more arid, is more suitable for camel, sheep

and goats. Yaks are also reared in more mountainous areas. Cattle is

protected from wildlife by huge and agressive dogs which sometimes chased

our van as we drove past a ger or a herd.

|

Toilets were about 50 m away in any

direction, behind a few taller blades of grass (sometimes there was

a hole in the ground, surrounded by a few planks to hide it a little).

As

we started our breakfast, the van accepted to start and our driver joined

us with a triumphal smile on his face. We never left before taking some

pictures, our hosts always proud to pose for us and with us in front

of their ger, on their motorbike or on their horse. I have never seen

people so happy to have photos taken. It will be difficult for reprints

to reach them, but it is worth a try, since they will be so happy to

receive some pictures. Then we were ready to set off.

Toilets were about 50 m away in any

direction, behind a few taller blades of grass (sometimes there was

a hole in the ground, surrounded by a few planks to hide it a little).

As

we started our breakfast, the van accepted to start and our driver joined

us with a triumphal smile on his face. We never left before taking some

pictures, our hosts always proud to pose for us and with us in front

of their ger, on their motorbike or on their horse. I have never seen

people so happy to have photos taken. It will be difficult for reprints

to reach them, but it is worth a try, since they will be so happy to

receive some pictures. Then we were ready to set off.